Fleets 'frustrated' with utilities slow to support electric truck charging

The issue of fleet electrification is often framed as a chicken-and-egg problem: Electric trucks can’t run without charging infrastructure, but how can the charging infrastructure be spec’d and installed before the trucks are operating?

But charging infrastructure consultant Charlie Allcock dismisses the dilemma.

“There is no chicken and egg here,” Allcock said, speaking at the recent T&D World Conference & Exhibition. “The chargers have to come first.”

Allcock retired from the public utility Portland General Electric in 2018 after focusing on the challenges of light-duty vehicle electrification and began his consulting business. An early client was Daimler Trucks North America, with headquarters in Portland, which had just launched the development of its electric trucks. Charging infrastructure, of course, is a critical component of putting commercial EVs to work.

See also: Slow and steady wins the race to zero emissions

“There's 3,000 utilities in the US and they're all different,” Allcock said. “What's a consumer-owned utility and what's a publicly owned utility, a co-op? So I've had a lot of fun helping an OEM and their customers understand utilities.”

Early on, truck OEMs were “nervous” about building EVs, Allcock noted, but no longer.

“They're all now comfortable, saying, ‘look, we can make this stuff,’” Allcock continued. “The fleets are saying, ‘we've tried them out, and we're also getting comfortable that we can see that electrification is in our future.’ The reality is that infrastructure has now emerged as the key issue in this transition.”

But, with orders now on the books and electric truck production ramping up, will the grid be ready?

“Right now, the utility industry is basically saying, ‘we'll see,’” Allcock said.

But that’s not what fleets looking to hit zero-emissions goals want to hear.

The reality, as Allcock explained, is that a fleet will go to a utility looking for some guidance on setting up charging stations. Fleets understand the infrastructure is going to be expensive, so they need to make sure they’re getting the right equipment in the best location. They’ll ask a utility to do a quick survey of some options. But utilities don’t work that way, or at least haven’t in the past. Utilities expect the customer to come in with site specs in hand—and they’ll get to it “whenever we can.”

See also: For those skeptical of EVs, Volvo offers ‘electromobility ecosystem’

And even when a fleet has done their homework and made a decision and submitted an application, a utility will come back with a “nine-month window” for energizing the site.

“You can see the frustration levels,” Allcock said. “The fleets don't want to take on a headache project today. They want to do something that's easy, that can get it started. They can learn from it and keep on going.”

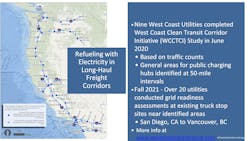

But that‘s just for a local, single-fleet charging depot. Allcock outlined a recent project that envisioned a 1,400-mile charging corridor from San Diego to Vancouver, B.C.

“I had the pleasure of working with 20 utilities all the way up and down the coast, and it was like herding all kinds of animals,” he said.

The hypothetical network called for 3.5-megawatt chargers every 50 miles by 2025 and 23-megawatt chargers by 2030. While 80% of the utilities said the 2025 “string of pearls” was doable, the amount of substation improvement work meant most of the 2030 project was not possible.

Additionally, the study revealed that “most utility folks did not know their counterparts at their neighboring utilities,” Allcock noted.

In another research project, Allcock did the math for the power requirements needed to support freight operations around the Ontario warehousing hub in Southern California. Using telematics data from Freightliner Class 8 trucks operating in the area and extrapolating based on Freightliner’s market share, the study concluded that servicing an all-electric Class 8 fleet in the district would need 1,500 megawatts of charging capacity. And that’s a lot of load. (For reference, 50 Class 8 trucks require 9 megawatts of charging capacity—about the same as the Empire State Building.)

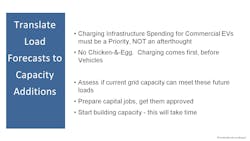

“Now, what are utilities doing to get ready for this future? Are you thinking about the capacity additions that you need to make?” Allcock posed. “So it's really coming down to distribution planners at utilities: They've never had to really do much of these ‘lumpy load’ additions that are coming.”

For example, large projects—such as new substations, sub-transmission lines, or transmission lines, requiring licensing, permitting, or land rights acquisition—can take 7 to 10 years, or more, according to Allcock.

In short, utilities need to be forecasting, planning, and investing now to have any hope of being ready for the clean truck future that’s coming.

“Yes, I'm talking about putting infrastructure in ahead of need—and I know what that means to a lot of utilities,” Allcock said. “But how else are we going to deal with this timing issue? You can make trucks a lot faster than the utilities can build the infrastructure. Now, what do we do as a collective society?”

It turns out, however, getting utilities to build infrastructure before it’s needed is a problem. A really big problem.

More to come.

Next: Grid not prepared for electric truck 'avalanche'