“What’s it worth?” is a question often asked. And when it comes to your trucks and trailers, the answer carries serious implications. Vehicles are the primary asset of almost all fleets, and their values weigh heavily on a fleet’s ability to conduct basic business functions like acquiring new equipment, obtaining operating credit lines, paying taxes, and even passing on ownership. Getting it right requires—and deserves—careful attention.

Fleets get equipment valuations as part of a lease versus buy decision, for insurance reasons and for purposes of internal costing, for instance. Or they may use them to create consistent financial reports on the value of their business. Passing the business on to the next generation or selling it involves asset valuation, as does the less pleasant process of bankruptcy. Taxing agencies and bank loan officials require asset valuation, and settlement of insurance claims often revolve around it.

“Valuation” is the equity (or lack of it) in an asset at a given time, so it stands to reason that the worth of something would be an exact figure and the process for determining it mathematically precise and fixed. This is not the case at all.

“There are several different reasons to do valuations,” says Jake Civitts, director of national accounts for Paccar Financial Corp., “and they may each serve a different purpose and be calculated using different valuation models.”

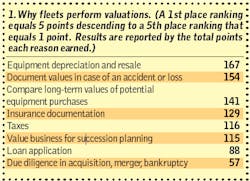

According to Fleet Owner’s survey on valuation, the number-one reason fleets have valuations performed on their assets is for purposes of depreciation and resale, followed closely by the need to document value for insurance purposes, to assess the relative worth of one potential purchase option versus another, and for taxes. Companies also do valuations as part of succession planning, to obtain credit, and as part of due diligence tied to other business transactions, such as acquisitions or bankruptcy (box 1).

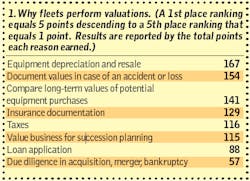

The problem is that there can be as many different possible valuations for a given asset as there are reasons to establish valuation and entities to assess it. When we asked fleets where they go for equipment valuations (box 2), dealerships and published guides like a “blue book” were cited by more than half the respondents. But most of those answering the survey indicated multiple valuation sources that also included insurers, leasing companies, banks and tax agencies. Perhaps most telling about the broad range of approaches to obtaining valuations, almost 14% chose the “other” category, writing in sources that ranged from advertisements to maintenance files to “myself.”

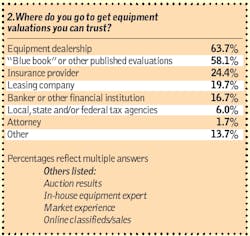

As might be expected, with multiple sources come multiple answers. Over one-third of the fleets surveyed said they’d encountered contested valuations between two or more of those sources (box 3).

Asked to briefly explain who disagreed and how the disagreement was settled, the widely varied answers reinforced the belief that equipment valuation uses are broad and sources for those valuations are all too often informal, incomplete or lacking transparency. Examples included values provided by guides that didn’t account for regional market differences or specialized equipment specifications, differences between claim settlement offers from insurers and the cost of replacement equipment, and the negotiating difference of opinion on value between sellers and buyers of used equipment.

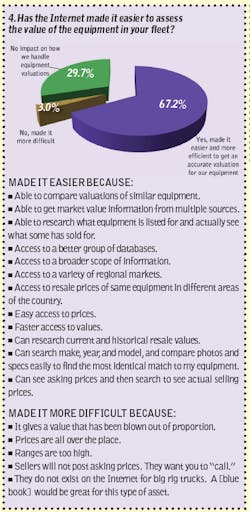

As it has in so many areas of business, the Internet is proving to be a disruptive technology when it comes to truck and trailer valuations, both improving broad access to information on equipment values as well as creating some new pitfalls. Over two-thirds of the fleets in the survey said searchable online information available through the Internet has made it easier and more efficient to get accurate equipment valuations (box 4).

Distilling the write-in answers, fleets like the ability to quickly see many databases of used equipment. It lets them account for regional differences in specific equipment prices, find equipment with specs more closely matching their own equipment, and generally cast a wider net that delivers more information and leads to a more accurate picture of asset values for their specific equipment at any given time. A number of respondents also liked the ability to compare actual sales prices for used equipment with asking prices.

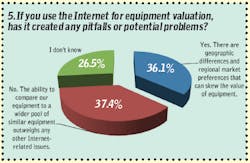

Opinions on the downside of Internet valuation centered on the credibility or applicability of the information (box 5). Over 36% indicated that unwary or inexperienced users of that information might not recognize unfamiliar regional requirements or operational conditions that have a significant impact on equipment value. Wide value fluctuations from various online sources were also identified as making accurate valuation more difficult.

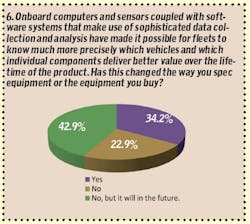

Our final two survey questions looked at how more accurate valuations may be influencing fleet buying decisions. Roughly one-third of respondents said access to more detailed equipment operating data from onboard sensors coupled with more sophisticated data analysis tools now allows them to identify vehicles and components that have lower lifetime operating costs, and therefore deliver better residuals and more accurate valuations. And another 43% said they expect to use such detailed analysis in the future (box 6).

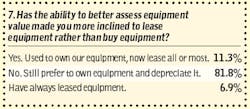

The final question (box 7) asked if better access to more accurate equipment valuations had an impact on lease versus buy decisions. The majority of respondents indicated that they still prefer to own and depreciate equipment, but a sizeable number (11.3%) said a fuller understanding of asset valuations had converted them to leasing.

About the Author

Wendy Leavitt

Wendy Leavitt is a former FleetOwner editor who wrote for the publication from 1998 to 2021.

Jim Mele

Jim Mele is a former longtime editor-in-chief of FleetOwner. He joined the magazine in 1986 and served as chief editor from 1999 to 2017.