The latest federal greenhouse gas emissions standards introduce tighter carbon dioxide emissions limits. However, many in the industry call it an EV mandate, including the American Trucking Associations, the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, and the Automotive Dealers Association.

“This regulation is actually saying: ‘Thou must have a different powertrain.’ You can’t get to GHG3 doing improvements and changes to regular diesel internal combustion or using a hybrid,” Ann Rundle, VP of ACT Research, told FleetOwner.

See also: Trucking industry reacts to GHG3 rule pushing zero-emission adoption

Others, including EPA and legal commentators, say the rule is certainly not an EV mandate.

Is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s latest emissions rule—Greenhouse Gas Emissions Standards for Heavy-Duty Vehicles-Phase 3—secretly an EV sales requirement?

The answer lies in a key tool for EPA emissions compliance—the Averaging, Banking and Trading (ABT) program.

What is ABT?

Averaging, Banking and Trading is a decades-long regulatory strategy that makes emissions compliance a bit more flexible. Under an ABT program, regulators can measure emissions compliance through a manufacturer’s sum of emission credits for a specific type of equipment.

Manufacturers following ABT can average emissions performance across several comparable equipment models so that low-emissions models can compensate for high-emissions models. The weighted “average” emissions across vehicles of the same type, then, would still be compliant with emissions standards.

Manufacturers can also bank/trade their emission credits, allowing some of their equipment models to produce higher emissions for several years.

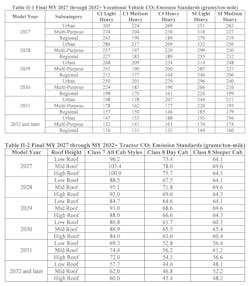

ABT generally only applies to models of the same type, which EPA calls an "averaging set." This differentiates between light heavy-duty (Classes 2b-5) vehicles, heavy heavy-duty (Class 8) vehicles, engine types, and so on.

The ABT approach makes sense when regulating vehicles. Trucks and engines have multi-year redesign cycles and don’t always meet exact emissions standards. With ABT, manufacturers can make a few lower-emissions models to compensate for their higher-emissions models.

“In any given model year, some vehicles will be ‘credit generators,’ over-performing compared to their respective CO2 emission standards in that model year,” EPA explained in its GHG3 final rule. “While other vehicles will be ‘debit generators’ and under-performing against their standards.”

How ABT allows for high-emissions vehicles

Since Phase 1 of the HD GHG standards, EPA’s ABT program has allowed heavy-duty vehicle manufacturers to still develop vehicles and engines that do not meet the new emissions standards.

According to EPA, manufacturers today commonly use ABT to comply with the heavy-duty GHG Phase 2 requirements: In model year 2022, 93% of certified vehicle families used ABT, and 73% of manufacturers used ABT to certify some of their vehicle families.

Here is a simplified explanation of how vehicles can earn or cost ABT credits:

Manufacturers group their vehicles into "families" (or subfamilies) and designate a family emission limit (FEL) for that group. Every vehicle in the family must comply with its designated FEL. If the FEL is lower than EPA’s emissions standard, the family of vehicles generates emissions credits for the manufacturer; if the FEL is higher, the vehicles generate debits for the manufacturer.

Banking and trading are important, but the first letter of ABT is most relevant here. Averaging is the process where a manufacturer earns credits from a lower-emission vehicle family in order to offset the debits from a higher-emission vehicle family. This only works within a shared vehicle type: the EPA-designated ‘averaging set.’ Class 6 EVs cannot compensate for Class 8 diesel tractors (with some exceptions).

The total mix of credit-generating and debit-generating vehicle families, averaged and weighted by sales performance, is how EPA determines a manufacturer’s GHG3 compliance within an averaging set.

Juggling various vehicles’ credit or debit generation is a key part of how OEMs comply with GHG emissions standards. A manufacturer’s unique approach to these acrobatics is called its compliance strategy.

Greater incentive for electric trucks

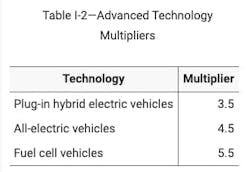

BEVs produce zero grams per ton-mile under GHG3, but the ABT credit incentive for electric trucks goes beyond that. EPA also grants an emissions credit multiplier for using electric vehicles, making an even greater incentive for EVs as a GHG3 compliance strategy.

EPA says it designed these credit multipliers to help compensate for the higher costs of EVs and the heavy-duty sector’s reluctance to adopt advanced technologies.

GHG Phase 3 uses the same credit multiplier from Phase 2: Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles can produce 3.5x credits, all-electric vehicles can produce 4.5x credits, and fuel cell vehicles can produce 5.5x credits.

However, these multipliers only work for the first few years of GHG3. Model years 2030 and later do not enjoy advanced technology credit multipliers. EPA also has new limitations on how manufacturers can use these credits.

GHG3 assumes major ZEV adoption by 2032

So, manufacturers have an easier time complying with GHG3 if they choose to sell EVs within a certain averaging set (e.g., among Class 8 tractors). Until MY 2030, that incentive is several times greater.

But the regulation may go beyond mere incentives to push EV adoption. EPA wrote GHG3 under the assumption of widespread ZEV adoption in a few years.

“EPA anticipates most if not all manufacturers will include credits generated by BEVs and FCEVs as part of their compliance strategies, even if those credits are obtained from other manufacturers,” EPA said in the GHG3 final rule.

In 2032, when GHG3’s standards reach the lowest level, EPA even states that “it is possible that only BEVs, FCEVs, PHEVs, and H2-ICE vehicles are generating positive credits, and other ICE vehicles generate varying levels of deficits.”

GHG3 does not require any fixed percentage of EV sales but does base its requirements on an expectation that “most if not all” manufacturers will use EVs in their compliance strategy.

Critics of the rule call it an "EV mandate" for this reason.

About the Author

Jeremy Wolfe

Editor

Editor Jeremy Wolfe joined the FleetOwner team in February 2024. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point with majors in English and Philosophy. He previously served as Editor for Endeavor Business Media's Water Group publications.