Diesel trucks may get new life in electrified world

Over the next two decades, the electric truck sector that comprises a few measly percentage points of total commercial vehicle market share will become a dominant force in transportation.

That's not an endorsement, mind you, as the technology has not been deployed on a wide enough basis to truly know if they will benefit the industry, economy, or the environment, but the momentum is undeniable.

Seven original equipment manufacturers have pledged to phase out diesel engines in Europe by 2040, while 15 states in the U.S. have developed escalating quotas on how many new vehicle sales must be zero emissions over the next several years to reach carbon neutrality. California specifically is eyeing 100% zero-emission passenger cars and light trucks by 2035, and 100% medium- and heavy-duty truck sales by 2045, which is spelled out in Gov. Gavin Newsom’s Executive Order N-79-20.

Through sweeping infrastructure proposals and the mantra of “Build back better,” the Biden Administration is intent on making EVs ubiquitous across all 50 states to address climate change. How fast that happens depends on customer acceptance, scaling at the manufacturing level, and charging station buildout, but one thing seems certain: electrification is coming to commercial transportation.

According to Sandy Munro, CEO of Munro & Associates, battery-electric or hybrid-electric powertrains will comprise more than half of the commercial and off-highway powertrain market by 2028.

It's a big change, but on the plus side, electricity costs less than gas or diesel fuel, electric trucks require less maintenance, and the ride is smoother and quieter. Negative factors include a far shorter period between recharging (battery-electric trucks may get 200-mile range, versus 2,000 miles between diesel fill-ups), the need for installing charging infrastructure, and higher initial cost, to name a few.

On that last point, a startup called Trova Commercial Vehicles, founded and run by former longtime Volvo Group executive Patrick Collignon, has a plan to lower initial adoption cost: diesel-to-electric conversion of existing Class 7-8 diesel trucks.

“Over the past year, we’ve developed our rolling chassis as a ‘skateboard’ solution for converting existing heavy-duty trucks to electric power at a much lower cost than buying a new EV,” says Patrick Collignon, TrovaCV founder and CEO. “Our D2E package combines the latest electric driveline technology with a completely new chassis thoughtfully designed from the ground up specifically for EV components. Also, our conversion process is being engineered to deliver rapid volume production, rather than the slow build of a typical mom-and-pop converter.”

TrovaCV is targeting a price tag two-thirds less than that of a new electric truck. If a new electric truck costs $300,000, an electrified TrovaCV truck would be $200,000. The process could take as little as 48 hours, Collignon projected.

“Yesterday, there was absolutely no real underlying reason why you would you change out your driveline," Collignon, CEO of the one-year-old startup, told FleetOwner. “Why would you do that? In today's world, there's an absolute opportunity.”

These trucks will ideally be 5 to 7 years old, an age when components require replacement and remanufacturing. TrovaCV and/or potential partners at the OEM and upfitter level will replace the diesel powertrain and aftertreatment components with a battery-electric drivetrain that offers a 200-mile range.

“Right now we can package 300-kilowatt hours of energy inside our chassis,” Collignon said. “The aim has been to maximize and finding ways to maximize our energy density inside the chassis.” Further testing on the impacts of topography, cooling and other limiting factors will dictate how efficient the driveline will be.

Product rollout could start in 2022, but Collignon acknowledged that they haven’t settled on a production site and are working out partnerships for long-term success.

“This could be a strategic choice for a large OEM to partner with Trova to get into the EV market more rapidly at a lower cost,” Collignon said.

FleetOwner reached out to Munro about his thoughts on the driveline conversion strategy.

“As far as the market for conversions on older diesel Class 8 trucks will be relatively small,” Munro said, which aligns with Collignon’s own estimates. “This will be due to the fact that the availability of conversion parts such as batteries, motors, and electronics will be scarce and very costly. There are huge issues with battery availability.”

Addressing environmental issues

While availability and supply are areas TrovaCV wants to address, governmental bodies seem more intent on just making fleets adopt as soon as possible—or else.

Collignon pointed out that in some areas, a company will soon be penalized if they do not reduce emissions. In May, the South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD) issued Rule 2305 to mitigate “indirect sources” of emissions at warehouses from heavy-duty trucks and material handling equipment. The goal is to reduce warehouse emissions by 10 to 15%, and those who don’t follow the point system laid out by the rule “can choose to pay a mitigation fee.” That money will pay for cleaner trucks and charging/fueling stations in communities affected by the warehouse’s additional emissions.

The problem is, as Munro pointed out, there will be only so many batteries available.

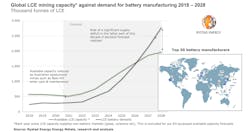

The industry will also have to address the inevitable shortage of lithium, the main material used in the batteries. According to Rystad Energy, that could begin in 2027 without more investment.

“A major disruption is brewing for electric vehicle manufacturers,” said James Ley, SVP at Rystad Energy’s Energy Metals team. “Although there is plenty of lithium to mine in the ground, the existing and planned projects will not be enough to meet demand for the metal. If more mining projects are not added to the pipeline quickly, the energy transition of road transport may need to slow down.”

With so many forces pressuring the onslaught of EVs, expanded mining is the likely outcome. That will create more emissions in the short term, though if EVs are able to be charged via renewable sources, the well-to-wheel emissions may be offset.

“We are all doing this for the greater benefit of the environment, but right now, EVs might not always be that pretty for the environment,” Collignon said. “I recognize that there's an ugliness to what we're doing today at the grand scheme.”

And even though Trova is targeting a small fraction of the overall industry, it is a small step in the right direction.

“We have to take these steps in order to get to the real thing, where we truly benefit the next generations, where we truly benefit our planet at large,” Collignon concluded.

About the Author

John Hitch

Editor

John Hitch is the editor-in-chief of Fleet Maintenance, providing maintenance management and technicians with the the latest information on the tools and strategies to keep their fleets' commercial vehicles moving. He is based out of Cleveland, Ohio, and was previously senior editor for FleetOwner. He previously wrote about manufacturing and advanced technology for IndustryWeek and New Equipment Digest.