Report: Fleets come out ahead on GHG reg’s costs, savings

Yes, truckers believe they can save the planet and save money at the same time. That’s according to a new report from the clean transportation organization CALSTART, and it comes as the EPA and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration hold hearings on the Obama administration’s proposed Phase II mileage and greenhouse gas emissions standards for trucks.

CALSTART commissioned the study to find out whether more aggressive fuel economy standards would help or hurt fleet-based businesses’ bottom lines. Speaking with Fleet Owner ahead of the official release Tuesday morning—and before he testifies at the EPA hearing in Long Beach, CA—Bill Van Amburg, CALSTART senior vice president, explained that report is based on a survey of truck fleets that looked into how they operate today and what their expectations and concerns are for the new regulation.

“And based on our survey, they believe that investing in more fuel-efficient trucks up front can be good for business in the long run,” Van Amburg said.

Indeed, the report finds that even when higher fuel economy standards result in more expensive trucks, fleets will come out ahead because they will save even more money at the pump.

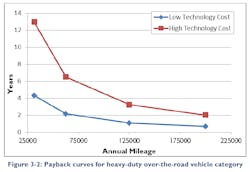

The payoff is quickest for over-the-road truckers who rack up the most miles. The study found switching to more fuel-efficient trucks could save up to $20,000 per year per truck, with a payback period for the extra investment in more fuel-efficient technology of as little as nine months.

[Editor’s Note: See the September issue of Fleet Owner magazine for a special supplement focused on the Phase II GHG proposal and the various new technologies and equipment being developed to meet the coming truck fuel efficiency standards.]

As for their feelings about the proposal, the survey found:

- 87 percent of fleet operators would support regulations that call for higher fuel economy.

- 86 percent said the upfront cost of a new vehicle is the biggest concern when making a purchasing decision.

- 89 percent said they would be willing to pay a higher upfront cost as long as there will be cost savings over the life of the vehicle.

But, Van Amburg noted, there is a caveat: Truckers are very concerned about reliability and maintenance costs, and want to see better data from manufacturers on these issues.

The problem, of course, is that scientific models and economic calculations don’t work well with estimates pulled from a crystal ball, complicating the modified life cycle cost (LCC) model that is at the heart of the report. Still, with the assistance of the National Association of Fleet Administrators (NAFA), CALSTART first validated the key metrics that go into the LCC based on actual fleet practice, then modified the model to account for unknown elements, such as future maintenance costs, and produced a fleet payback calculation.

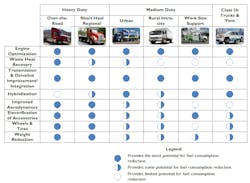

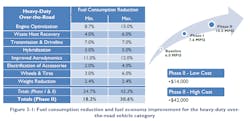

The analysis, which does not address trailers, is based on a selected range of technologies and their projected costs, which appear able to achieve the higher efficiencies (up to 40 percent reduction in fuel use) expected by 2025 and tailored to different vehicle-use profiles.

Van Amburg pointed out that the technologies, which look impressive together on paper, aren’t “additive,” meaning that some combinations will not deliver the full potential savings of each component—they just don’t work well together.

For OTR fleets, engine optimization and improved aerodynamics are estimated to provide the most fuel consumption reduction. The Phase II technology package cost is estimated to range from $14,000 to $42,000, and the model shows the payback period of a Phase II technology package capable of 24% fuel consumption reduction would run from one to three years, depending on vehicle miles and the price of fuel. (For this calculation, the EIA 2015 reference price for diesel of $3.28 per gallon was used.)

Also of note, Van Amburg explained that resale values were not included in the model, both to avoid “multiplying bad assumptions” and because, in setting up the life-cycle model, resale prices were found to be not nearly as significant fuel efficiency and maintenance costs.

He also suggested that the independent report is “not far off” from the EPA’s own payback estimates, and that the agency seems to be sensitive to fleet concerns over the reliability issues that plagued the development of NOx emissions technology through 2010.

And while environmental groups are pushing for a faster adoption schedule, Van Amburg anticipates EPA instead might increase the stringency levels but allow for the longer implementation path through 2027.

“When you really look at what’s driving the rule, it’s the need to reduce emissions because of climate change and carbon—and making sure we stay on a reasonable reduction path to cause some good things to happen,” Van Amburg said. “By the same token, the balancing act is how fast can this be moved through and really transition the fleets?”

Overall, he suggested the Class 8 targets are “reasonable” and “doable,” although there may be even more room for improvement in the vocational segment.

“We think our report addresses the payback opportunities: There really is a business case for saving fuel in a smart way,” Van Amburg said. “But we need everybody to be a little more focused on getting the maintenance and reliability issues right up front. The devil is in the details.”

About the Author

Kevin Jones 1

Editor

Kevin has served as editor-in-chief of Trailer/Body Builders magazine since 2017—just the third editor in the magazine’s 60 years. He is also editorial director for Endeavor Business Media’s Commercial Vehicle group, which includes FleetOwner, Bulk Transporter, Refrigerated Transporter, American Trucker, and Fleet Maintenance magazines and websites.