Diesel and gasoline taxes have received fresh attention this spring as state capitals and the federal government have looked to provide relief—albeit temporary in the form of fuel-tax “holidays”—in an environment of historically high prices on the distillates that are used by trucking and consumers.

By last fall, attention had turned away from these taxes—the federal levy on diesel is 24.3 cents while states add on varying amounts that average 39 cents per gallon—after President Joe Biden signed into law the massive $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which promises to flow $110 billion alone to road, bridge, and tunnel repairs and improvements nationwide. The Highway Trust Fund (HTF), which is filled by the federal diesel tax as well as the 18.4-cent-per-gallon levy on gasoline, usually funds these types of investments, but the pressure was off the HTF at the time.

See also: Diesel level for second straight week

Then Russia—a major energy exporter, mostly to Europe but a fraction to the United States—commenced its bloody invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, sending shock through oil and distillate markets that had already seen prices increase steadily since last year. The U.S. government on March 7 reported the largest weekly diesel price spike ever—74.5 cents per gallon—and nationwide prices for trucking’s main fuel have remained historically high since ($5.571 per gallon on May 23), or more than $2.30 per gallon more than they were last year. Gasoline, while cheaper than diesel, is almost $1.58 more than a year ago, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), which tracks the fuel-price trends.

Mixed bag of relief

On Capitol Hill, U.S. Senate Democrats in February introduced the Gas Tax Relief Act, which would pause the federal gasoline tax until Jan. 1, 2023. The bill there was sent to committee and hasn’t moved since. A companion bill in the U.S. House was referred to committee as well, but it also hasn’t moved.

Several states have acted in recent months to provide fuel-tax relief, some of which benefits trucking.

Georgia’s fuel-tax holiday, which began March 18, helps consumers and commercial fleets. Both received relief through May 31 from Georgia’s 32.6-cent diesel tax and its 29.1-cent tax on gas.

See also: How to maximize fuel economy

Maryland was the first state to provide relief, but an attempt there to extend its fuel-tax break past April 16 to Memorial Day failed. Maryland adjusts its fuel taxes each July based on the Consumer Price Index. Since last July 1, the diesel tax rate there was 36.85 cents per gallon, while the levy on gasoline has been 36.1 cents. Collection of those taxes was suspended in Maryland for 30 days.

In Connecticut, a three-month holiday from the state’s 25-cent-per-gallon gas tax began on April 1 and runs through June 30, but the tax holiday there does not affect the state’s 41.1-cent excise tax on diesel. Estimates show that the gas-tax holiday will cost Connecticut about $90 million.

Long-debated fuel-tax shortages

Once upon a time, when diesel prices were lower—they hovered from about $2 to just above $3 per gallon from 2005 to 2019, pausing for momentary jumps above $4 in 2008, 2011, and 2014, according to EIA historical data—the trucking industry lobbied heavily for an increase in the federal fuel taxes, which have stayed at their present levels since the Clinton administration in 1993 and have not budged.

Long before the government stepped in last year with the massive infrastructure bill, stakeholders worried that the Highway Trust Fund, financed by the too low federal fuel taxes, could not sustain the level of road and bridge repair and improvement that the nation needs. The U.S. ranks just 13th in the world for the quality of its infrastructure, according to a 2019 Statista survey.

These stakeholders still have these concerns, though “the infrastructure bill kicked this can down the road a little bit. The urgency seems to be less than it was,” Mike Roeth, executive director of the North American Council for Freight Efficiency (NACFE), a leading organization in freight transportation fuel savings and sustainability, told FleetOwner.

“What got us into this problem in the first place was we were behind the eight ball. We didn’t raise fuel taxes in the first place. There’s still revenue there that is not being captured now. You do still run the risk of falling behind on those,” Heller said.

He pointed out that the landmark infrastructure law, which contains $550 billion in new spending above baseline levels, is set to expire after five years—when an administration and Congress of another political party with different priorities could be in power in Washington.

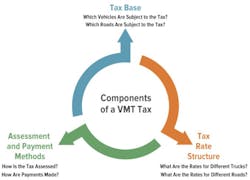

See also: A closer look at VMT tax

Then, the onus to fund roads, bridges, and tunnels would be back on the Highway Trust Fund, and the fuel taxes that fund the HTF will still be too low. States, meanwhile, have increased their own taxes on diesel and gasoline many times since the Hubble Space Telescope was fixed and the Colorado Rockies and Florida Marlins joined Major League Baseball.

According to a 2019 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report on the feasibility on a vehicle miles-traveled (VMT) tax, in almost every year since 2001, spending from the HTF has exceeded those tax revenues; in 2017, for example, the fund had about $41 billion in revenues but $54 billion in outlays. To help cover those shortfalls, the fund has received $144 billion in transfers, primarily from the U.S. Treasury’s general fund. CBO had projected that the HTF would be exhausted by this year.

And on the other side of the equation, the cost per mile of a lane of new highway has gone nothing but up, Heller noted, to an estimated $800,000. “We’re not talking about nickel-and-dime stuff; we’re talking about real dollars. The dollars don’t go as far as they used to. It’s the federal aspect of it that’s becoming problematic.”

EVs and a VMT tax

Electric vehicles are coming—sooner it seems than later, according to federal data and industry trends.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy reported sales of new light-duty EVs, including plug-in hybrids, nearly doubled from 308,000 in 2020 to 608,000 last year. However, sales of light-duty fossil fuel-burning vehicles in the same commercial classes only increased 3% during that same period. According to the same government office, 13 new EV battery plants are planned in the U.S. within the next five years in addition to the plants that are already in operation.

More studies show that the EV population is small now, representing less than 1% of the total commercial vehicles on the road in the U.S. and Canada. But projections are that by 2027, EVs will grow to 22% of the market and will reach 40% by 2035. At that point they will grow at 3% per year until 2040. The Biden administration has called for half of all U.S. vehicle sales—cars, commercial vehicles, school buses, transit, everything—to be ZEVs, or zero-emission vehicles, in just eight years from now.

But EVs burn nothing, or in the case of their hybrid counterparts, next to nothing. Out of fairness, how would the federal government tax these vehicles as internal combustion engines (ICE) are taxed today and bring equity to the system? The VMT tax has long been floated as a solution. Even as ICE vehicles have become increasingly fuel efficient, gas and diesel tax revenue has been lost because they burn less.

In the U.S., a VMT fee exists today only as part of a limited program for about 5,000 volunteers in Oregon and for trucks in Illinois. Other nations—Germany, Austria, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Belgium, Russia, and Switzerland—utilize various VMT fees, limited to trucks. New Zealand’s system, known as the Road User Charge, applies to all heavy vehicles and diesel-powered cars. Bulgaria also is developing a truck-based system. And with the British government banning the sale of non-electric cars after 2030, a VMT tax is being considered in place of fuel-duty revenue.

Studies show that a VMT tax in the U.S. could be much more efficient and could collect many more dollars for the Highway Trust Fund than the current federal taxing regimen does.

One report, commissioned by the American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI), showed that a VMT tax assessed on 272 million private vehicles could result in the collection of more than $20 billion annually—or 300 times more than the federal fuel-tax system. According to that same March 2021 ATRI study, implementing a VMT collection system would be costly—as much as $20 billion—in hardware and administration, so such a system does not come without strings attached.

See also: The high-priced reality of a national VMT tax

The Biden administration favors a VMT fee as a fairer funding mechanism for a future with mixed vehicle options—ICE, hybrids, electrics.

“With policymakers preparing to lay out a vision for the future of America’s infrastructure, ATRI’s analysis could not come at a more critical time,” American Trucking Associations President and CEO Chris Spear said when ATRI’s study was released. “Most experts agree that some sort of VMT system is a part of that future, and ATRI’s report makes clear that implementing it will take thoughtful leadership, cooperation from stakeholders and a strong plan to transition away from current funding streams.”

But because of the 800-lb. gorilla that is the new infrastructure law, talk of a VMT taxing system also seems to have receded into the background, TCA’s Heller observed. But it won’t stay there, he said.

“We don’t hear a lot about VMT these days because the infrastructure bill just got passed,” he said. “At this point in time, we support the fuel-tax increase and to couple it to inflation. There are pilot programs right now that impact VMT, but the administrative costs are higher. Even as commercial trucking starts to explore electric vehicles, they still are putting that wear and tear on our roadways. The question is, how do we capture that?

NACFE’s Roeth said he believes that when the issues of inadequate federal fuel taxes and a VMT fee come to a head, after the excitement of the infrastructure law blows over, “this will get figured out. There are still very few electric vehicles out there. It will self-correct. It’ll get dealt with when it needs to get dealt with. It’ll have something to do with VMT.”

About the Author

Scott Achelpohl

Managing Editor

Scott Achelpohl is a former FleetOwner managing editor who wrote for the publication from 2021 to 2023. Since 2023, he has served as managing editor of Endeavor Business Media's Smart Industry, a FleetOwner affiliate.