“Do you think that the future of propulsion lies in the modification of the internal combustion engine? I think, at least for the long term, [we] are spitting into the wind. We already have an efficient IC [internal combustion] engine. I think we should be looking at other means of propulsion.” –Steve Grantham, maintenance supervisor for Allied Waste Services, which is now mergered with waste giant Republic Services

A long time reader of this blog and a frequent, insightful commentator, Steve Grantham posed the question above in reference to my post yesterday on the joint efforts by the Dept. of Energy (DOE), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and private industry to spur vehicle innovations.

Steve’s question – submitted within a longer comment – raises a very interesting point; for all intents and purposes, has the internal combustion engine, specifically the diesel model, run its course as an efficient method for vehicle propulsion? Is it time to replace it with something else?

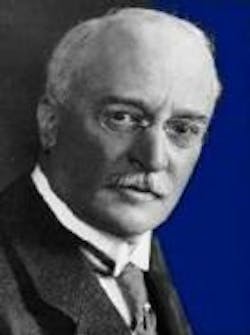

I don’t think so – especially where the diesel engine is concerned, even though its invention dates back over a century. The diesel, of course, takes its name from its inventor – Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel, a German engineer convinced there had to be a more efficient form of vehicle propulsion than the steam engines used by Gottlieb Daimler and Karl Benz to power the automobile they invented in 1887.

By 1893, Rudolf (seen here at right) worked out his own engine design, one that cleverly used extremely high air compression ratios -- creating over 1,000 degrees of heat -- to ignite fuel injected into the cylinder.

That’s a critical feat of engineering, I might add, because it totally eliminated the need for a “spark” to light off the fuel. That also makes a diesel engine extremely versatile in that ANY type of material can be used as fuel, Glenn Lysinger, chief compliance officer for Detroit Diesel Corp., told me a couple of years ago. “It’s the quality of the fuel that is important,” he explained. “If the fuel is made correctly, is of a consistent quality so it’ll burn evenly and not leave residue, the [diesel] engine is insensitive to where it came from.”

Yet at the end of the day it boils down to efficiency – especially in terms of fuel consumption. Rudolf Diesel got out a blank sheet of paper back in the 19th century because even the very best steam engines of his day (at the time, the only major power source for vehicles) were only 10% to 15% thermodynamically efficient – meaning up to 90% of the available energy in the fuel used to produce the steam to power the vehicles got wasted.

Rudolf’s invention, of course, did much better – and engineers over the more than 100 years since the ink dried on the patent for the diesel engine have made significant improvements. But emission controls of late are sending the diesel’s efficiency numbers in reverse. A few years ago, I talked to Jules Routbort about that very issue.

A senior scientist with Argonne National Laboratories – the DOE’s research arm – and technical program manager for heavy vehicle systems, Routbort explained to me that the peak thermal efficiency of a heavy truck diesel engine reached 54% in the late 1990s, but dropped to 40% by the time EGR [exhaust gas recirculation] were introduced to control diesel pollution back in 2002 and 2007. Though OEMs using selective catalytic reduction [SCR] technologies to meet the 2010 round of emission rules say it will allow engines to gain back some of that lost efficiency, they won’t get all the way back to that 54%.

So back to Grantham’s question – what’s next? Do we scrap the diesel entirely? I just don’t think so. I mean, the diesel is so interwoven into our daily life – powering trucks, cars, backup generators, you name it – that It would be hard, if not impossible, to replace. Nothing else has the efficiency and durability of the engine (though, as Grantham mentioned, that durability and ease of maintenance is way, WAY down compared to earlier models).

Different fuels seem to offer a better path – as do some new designs. The Scuderi Group, for example, is in the midst of testing out a new thermodynamic engine process called “Firing After Top Dead Center” which (obviously) it’s dubbed the “Scuderi Cycle.” Originally conceived and designed by Carmelo Scuderi (1925-2002), the Scuderi engine is expected to produce up to 80% fewer toxins than a typical internal combustion engine while posting gains in efficiency – without all the aftertreatment systems.

In a nutshell, the Scuderi split-cycle design divides the four strokes of a conventional combustion cycle over two paired cylinders: one intake/compression cylinder and one power/exhaust cylinder. By firing after top-dead center, it produces highly efficient, cleaner combustion with one cylinder and compressed air in the other, the company noted.

Unlike conventional engines that require two crankshaft revolutions to complete a single combustion cycle, the Scuderi Engine requires just one. Besides the improvements in efficiency and emissions, studies show that the Scuderi Cycle is capable of producing more torque than conventional gasoline and diesel engines, the firm said.

Right now, the company is testing a naturally aspirated, 1-liter gasoline-powered prototype is currently which the company says is expected to reach efficiency gains of 5% to 10% more than any conventional gasoline engine on the road today. When fully developed with its turbocharged and Air-Hybrid components, Sal Scuderi (seen here at right), president of the Scuderi Group, told me the engine is expected to achieve efficiency levels of 25% to 50% percent higher.

Sal also told me in an interview a few months back when testing got started that his father’s new design is definitely applicable to diesel engines, and that once testing is completed on the gasoline version, a diesel engine prototype is next.

“Preliminary test results are very encouraging,” he explained. “The pressure curves produced from the combustion process of firing after top dead center are showing excellent results and torque levels remain very strong.”

Is something like this the key to revitalizing the future of the diesel engine? At the moment, only maybe, for as we all know what works well in the lab doesn’t always perform as well on the road. But the Scuderi Cycle and other innovations – the diesel-electric hybrid powertrain, for one – seem to offer some good options for boosting the efficiency of the diesel engine, thus keeping it a viable option for future transportation needs.