Key takeaways:

- Fleet electrification relies on regulatory support, customer demand, and affordability—ZEV ownership costs need to compete with traditional vehicles to be viable.

- Zero-emission vehicle costs could decrease by up to 30% through advances in battery tech and manufacturing.

- Improvements in lithium-ion iron phosphate batteries and initiatives like Amplify Cell Technologies aim to lower costs and enhance domestic production.

The benefits of fleet electrification continue to be outweighed by its hurdles. The upfront cost of battery-electric vehicles remains a particular challenge.

Zero-emission commercial vehicles are expensive. It’s a significant reason why ZEV adoption is stalling, Congress voted to revoke CARB waivers, and CARB states got cold feet.

However, that’s not the final word on ZEV. Partners with McKinsey & Company estimate that OEMs can reduce the cost of zero-emission trucks by as much as 30% in the near future.

That cost reduction would come from many areas—supply chain optimization, warranty reductions, and more. But the greatest price improvement could rest in the battery pack.

“We see different battery chemistries and technologies allowing us to take almost half the cost of the battery pack,” Moritz Rittstieg, a partner with McKinsey & Company, told industry media at the Fosgard House of Journalists during the Advanced Clean Transportation Expo in Anaheim. “We see significant improvements in speed of charging and costs going down much faster than projected.”

Why fleets adopt EVs

Three major motives for fleet electrification are regulations, customer demand, and affordability.

Regulatory support for electrification will likely continue to weaken for several years in the U.S., leaving customer demand and affordability as the main drivers for fleet EV adoption.

See also: Congress kills CARB’s ACT, Omnibus waivers

“There are currently headwinds through regulations and so on,” Rittstieg said. “We still think there is tremendous value, and a lot of our executive clients agree, to find alternative ways to make it happen now and not push off the timelines.”

Customer demand is growing. Carbon emission reductions are increasingly popular among some of the largest U.S. companies, including Amazon, Microsoft, Phillips, and many more.

Much more important, though, is affordability: If the total cost of ownership for a commercial zero-emission vehicle can match (or even fall below) the TCO of an internal combustion engine vehicle, fleets that can adopt ZEVs will almost certainly do so.

“Once that [TCO] happens, then you’re no longer reliant on regulation for adoption,” Dilip Bhattacharjee, partner for McKinsey & Company, told journalists. “Fleets will do it because they make money.”

Currently, the commercial ZEV cost of ownership is above that of diesel vehicles for most fleets. McKinsey & Company estimates that fleet ZEV TCOs are 30-50% higher than ICE vehicles running diesel.

The upfront cost of an EV, which the firm said is about 35% of a battery-electric vehicle’s TCO, is significantly higher compared to diesel, according to the firm. A diesel heavy-duty day cab could cost roughly $150,000 in 2024, while the ZEV equivalent could cost $250,000 on the low end to as much as $400,000—roughly a 100% markup.

“The OEM pricing has to come down,” Rittstieg said. “They cost OEMs way too much money.”

Rittsieg suggested that OEMs could reduce upfront EV prices from $400,000 down to as little $285,000 through three main areas:

- Battery packs (subsidies, battery chemistry, and design)

- Manufacturing (efficiency improvements)

- Scaling (economies of scale, supply chain optimization)

Perhaps the most significant upfront cost improvement is taking place in the battery packs. According to Rittstieg, battery pricing optimization could cut the cost of the battery pack by almost half. For a $400,000 truck, that could be a reduction of $60,000—about 15% of the total upfront cost.

How OEMs can reduce battery costs

Those battery cost improvements are elevating an underdog of EV battery chemistries: lithium-ion iron phosphate (LFP) batteries.

For years, LFP had a reputation for being cheaper but less energy-dense than batteries built with more expensive metals, such as nickel and cobalt. Though it was worse at storing energy, LFP had potential: The chemistry uses plentiful and affordable ingredients, has a greater lifecycle performance, and is less prone to catching fire.

Recent major manufacturing improvements, such as Chinese company BYD’s development of cell-to-pack technology, increased LFP packs’ energy density. The addition of manganese to LFP, referred to as LMFP, further closed the performance gap.

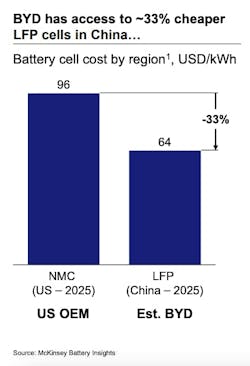

However, those cost reductions were not achieved by U.S. OEMs but by Chinese manufacturers.

“The only issue is that most of the technology relevant for commercial vehicles has to come out of China,” Rittstieg said.

The U.S. depends heavily on imports to meet LFP battery demand, and China is its largest provider. Commercial OEMs have an opportunity to lower EV costs by moving this improved battery production to North America.

“We’re seeing some of that technology come to the U.S.,” Rittstieg said, which “will massively bring down the cost.”

The joint venture: Amplify Cell Technologies

Thankfully, major U.S. OEMs are already bringing LMFP battery production across the Pacific.

Amplify Cell Technologies is a joint venture by some of the nation’s largest trucking equipment manufacturers—Daimler Truck, Paccar, and Accelera by Cummins—to build more affordable commercial EV batteries.

Though battery production for passenger vehicles already reached significant cost reductions due to scale in North America, it is not yet the case for heavier commercial vehicle batteries.

“We realized what was being produced at scale today wasn’t going to meet the needs of you all,” Brian Wilson, general manager of eMobility for Accelera, said during a roundtable featuring Amplify and its partners at the Advanced Clean Transportation Expo in California.

Medium- and heavy-duty battery packs must differ significantly from passenger vehicles to fit fleets’ demands for power, lifecycle, durability, and energy capacity. Looking at the available battery chemistries, the OEMs concluded that LMFP, with its recent technology improvements, was best suited for the job.

“The only phosphate batteries that were mature enough to do this were China-based,” John Rich, VP and CTO of Paccar, said at the roundtable.

Building those phosphate batteries in the U.S. could help the OEMs scale production and reduce costs.

“We’re well on the way to build a plant that is at the required scale—and we have the localization, suppliers, and supply chain—that enables those costs to be reduced,” Kel Kearns, CEO of Amplify, said.

The joint venture is currently building a 21 GWh factory in Mississippi to produce commercial battery cells for heavy- and medium-duty vehicles. The company broke ground on the plant in mid-2024 and plans to begin production in 2027.

Kearns forecasted commercial EV battery costs to fall significantly below the long-sought-after battery price of $100/kWh.

“The $100/kWh is not going to be a stable target.” Kearns said, estimating it will continue to reduce to “numbers in the future as low as $30.”

About the Author

Jeremy Wolfe

Editor

Editor Jeremy Wolfe joined the FleetOwner team in February 2024. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point with majors in English and Philosophy. He previously served as Editor for Endeavor Business Media's Water Group publications.